Stress

Disaster: A Psychologist’s Perspective

The Lessons Learned and the Birth of a New Field of Study

Posted October 3, 2017

A disaster is often defined as a critical incident whose negative impact is characterized by great physical damage, loss of life, or hardship. But disasters can also result in great psychological suffering as well.

On March 28, 1979, nuclear reactor number 2 at the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station in Pennsylvania experienced a partial meltdown of its uranium fuel rods. Fortunately the containment vessel was not compromised. Nevertheless, as a result of this meltdown, radioactive gases were released into the atmosphere. This was my first professional response to a disaster. I’m not an engineer nor am I a nuclear physicist. I’m a psychologist. Authorities in Pennsylvania asked me to travel to Three Mile Island to assist those in the Three Mile Island community cope with the psychological impact of the disaster. This was over a decade before the field of disaster mental health would be largely founded. The idea of sending a psychologist to assist a community in its recovery was a novel, if not, seminal thought. Sadly, not everyone was thrilled about my being there. After all, what was all the fuss? No one died, and no one was even injured. It seemed to me, and later research would confirm, there was significant stress and anxiety amongst the people who lived close to the reactors. There was also significant denial.

In 1992, Following the seminal work of the International Critical Incident Stress Foundation (a United Nations-affiliated agency created to support the acute psychological health of emergency workers) the American Red Cross fostered the development of a nationwide network of psychological crisis intervention teams which would be deployed along with traditional Red Cross disaster response personnel. These teams were to provide acute psychological support to Red Cross workers, as well as civilian disaster survivors who might be experiencing acute psychological distress. And so the field of disaster psychology was born. I served as founding co-chair of the Central Maryland Red Cross disaster mental health committee.

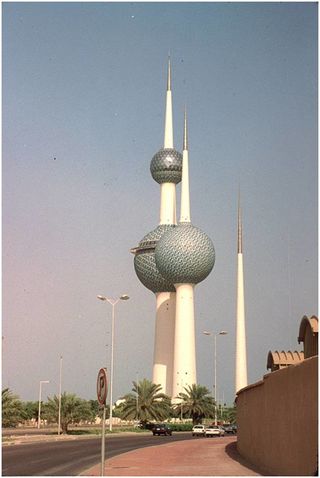

From 1995 to 2001, I was Senior Advisor to the Office of His Highness the Amir of Kuwait. I was appointed to this position to develop programs to foster resiliency in the community of Kuwaiti citizens who lived through the invasion and occupation of Kuwait by Iraqi forces during the first Gulf War. At that time, there was not a widespread acceptance of the need for mental health services in general, but the adverse psychological consequences of the occupation, such as reactive depression, grief, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), were so apparent the need for psychological interventions throughout the Kuwaiti community was self-evident.

By September 11th, 2001, attitudes had progressed even further. The attacks on the World Trade Center underscored the importance of providing acute psychological support (psychological crisis intervention) to not only civilians, but to emergency workers, as well. I worked in New York City and New Jersey for over a year primarily assisting law enforcement personnel.

What lessons did these early experiences teach me?

1) With every physical disaster, there will be a psychological disaster.

2) Psychological casualties will always far outnumber physical casualties.

3) Common reactions will include reactive depression, bereavement and grief, profuse generalized anxiety, and posttraumatic stress.

4) While those reactions are relatively common and will usually fade with time, those trained in psychological crisis intervention (think psychological first aid) can help communities, as well as emergency workers, accelerate natural resilience and help people bounce back from the pain associated with disasters more rapidly than might otherwise occur.

5) Communities never truly recover from disasters until a psychological infrastructure of resilience has been fostered (Everly & Lating, 2017)

As I left Kuwait in 2001 for the final time, I addressed the Kuwaiti Parliament and asserted that communities impacted by disaster will not recover until the spirit of resilience is nurtured. This is the job of the disaster psychologist.

(c) George S. Everly, Jr, PhD, 2017.

References

Everly, G.S. & Lating, J.M. (2017). The Johns Hopkins guide to psychological first aid. Balto: Johns Hopkins Press.